SUSTAINABILITY MUST MEAN DECOLONIZATION

Seven years ago, my relationship with fashion shifted from a practice of retail therapy and aligning with arbitrary notions of what was “in,” to a deeply personal exploration of my South Asian identity and decolonization.

I remember my beginnings in the world of sustainable fashion clearly. It was 2013, and I was just about to start my undergraduate career as a Journalism and International Studies student at University of California, Irvine. Growing up as the daughter of the diaspora, design and aesthetics had always been powerful tools for me to explore my South Asian heritage, and fashion was quickly becoming a realm to explore artistic expression. A few months later, the Rana Plaza Factory collapse happened.

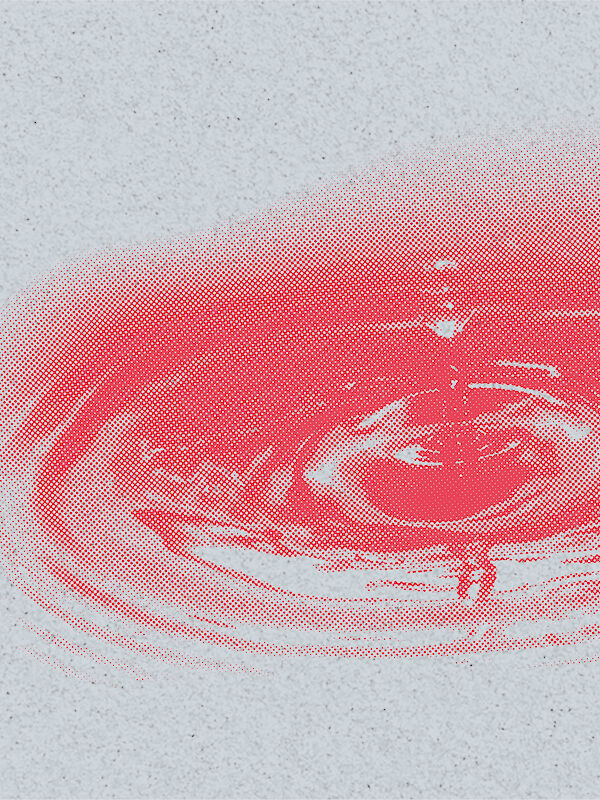

Rana Plaza was an eight-story garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, that was producing apparel for household name fashion brands. On April 23rd, 2013, structural cracks were identified in the building. However, due to pressure from upper management, workers were called into work the next day to finish orders for brands including Zara, Walmart, Benetton, and Mango. The next day, Rana Plaza framed one of the biggest industrial disasters of human history: an eight-story factory collapse that killed more than 1,132 workers and injured over 2,500.

Rana Plaza catalysed a new understanding of fashion for me. No longer was fashion just about a pretty dress. It was about the politics of labour, to the industry’s disproportionate burden upon communities of colour worldwide, notably, South Asia. But the fall of Rana Plaza also marked a key moment in the world of fashion and the sphere of sustainability and ethics.

What came next was the exponential rise of key words like sustainable or ethical fashion. At its best, brands differentiated themselves with fair pay, transparent supply chains, and eco-friendly materials. However, another insidious side of the sustainable fashion narrative was on the rise.

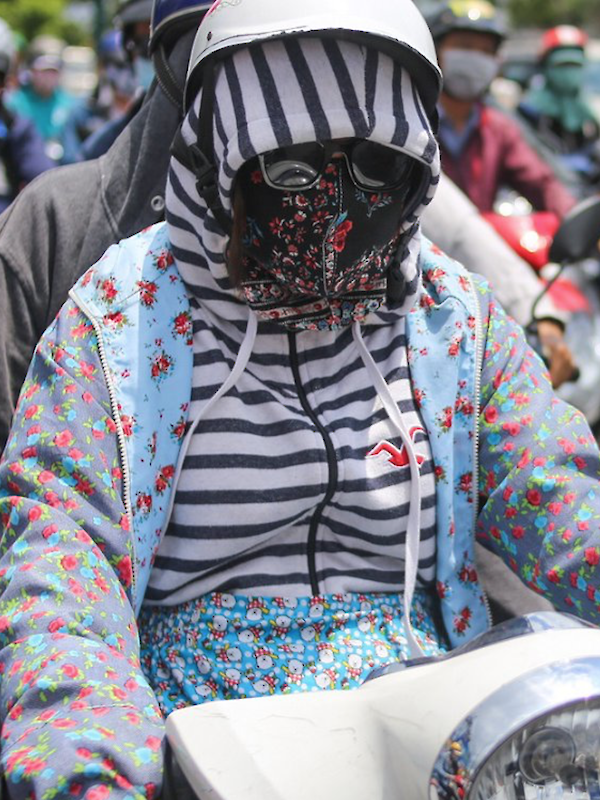

The sustainable fashion movement became one homogeneously led by well-off white people. The presence of women of colour was often tied to their labour. Apart from the blown-up black-and-white images of the women of colour who created the brand’s clothes, I was routinely the only woman of colour at sustainable fashion events.

The sustainable fashion narrative created a stark binary between the Global North and the Global South. In the Global North, the protagonist was often a white consumer who was able to buy into a culture of global moralism. In the Global South, it was the archetype of a poor woman whose fate rested in the hands of a white saviour. Sustainability, in many ways, was re-sold as a practice one had to buy into. Key sustainable fashion platitudes like ‘Vote With Your Dollar’ fuelled problematic ideas of how one could engage in the movement, and more importantly, who could engage in the movement: those who could afford it.

Let me be clear: conscious consumerism is important. However, the onus of ethics shouldn’t be solely on the individual, but rather on the industry that largely normalized violence as part of its business model. We must question the systems and structures that set the conditions for the fateful day of the Rana Plaza tragedy. The collapse was not an unpredictable disaster. It was simply the manifestation of a system that is rooted in growth at all costs, even human lives. Rana Plaza spoke to a deeper system of oppression, a system that was built on the oppression of black and brown bodies, based on an institutional form of racism inherited from a colonial past. What is the historical context that created a system that operates in this way?

The Colonial Fashion Model

Colonialism is often seen as a distant abstraction of the past. Yet, colonial mentalities and practices continue to reign supreme in how business operates today. When I speak of colonial practice in the fashion industry, I refer to systems that are predicated on the extraction and exploitation of resources, from raw materials to labour, as the means for infinite growth and success. Most of these resources are extracted precisely in nations destabilized from colonial violence.

Like many global industries that rely on production in the Global South for consumption by the Global North, the fashion industry is rooted in an unequal exchange. The unequal exchange is often the exchange of manufactured products, produced at shockingly low prices due to labour that costs near nothing, to be sold at higher margins in the Global North. We know this to be especially true for the fashion industry, as it’s largely operated on the Global Race to The Bottom — the idea that brands scramble to produce as fast as they can, as much as they can, as cheap as they can—which often means heading to the countries that are still reeling from the impacts of colonization, making them an especially vulnerable workforce (read: the propelling tool of exploitation).

The relics of a violent past and present are embedded throughout our modern world. As a South Asian woman coming from a culture colonized by the British Raj for two centuries, I often think about the jewellery the Queen of England still adorns, stolen from my part of the world, never to be returned. The colonizers today, much like the British Raj, are the brands themselves. Their business model has always been to head to the cheapest and poorest parts of the world. This is not because of infrastructure or better factories. This is simply because they are the cheapest frontiers left to extract from. In her article for the first Intervention of State of Fashion, Sandra Niessen describes these sites as sacrifice zones; places in the world whose vulnerable populations undergo resource extraction and exploitation for the sake of continued economic prosperity and growth.

Empires of Cotton

History shows us that textile and fashion production has fuelled these colonial empires, and the emergence of sacrifice zones. In 1664, the East India Company was established as the largest importer of cotton to Europe. A systematic plan was implemented to subdue the Indian textile industry and economy by coercing Indian farmers to abandon their farming of subsistence crops in favour of the cotton crop. Not only would this eventually subject farmers to a cycle of interest-laden debt, it would also eventually diminish the food supply greatly.

India was to constantly supply cotton that would be taken to Britain's Lancashire cotton mills and the market for British cloth, ensuring that the colonized remained subdued and profitable for the colonizer. India became an exporter of only raw material, that was only to be sold back in India at rates that left local spinners and weavers unable to afford the cotton required for their production. The extraction and destruction of artisanal industries and agricultural practices that the land could not sustain ensued.

What is important to note is the pattern of exploited labour around the world, and the positioning of Britain as the “workshop of the world”. British-manufactured cloth severely undermined the Indian cotton industry during the nineteenth century, due to the speed of the U.S. – British cotton production system, which was predicated with the use of slave labour in America.

Enslaved African people allowed White plantation owners in the South to garner insurmountable wealth from cotton. Exploited labour and agricultural dexterity set the groundwork for the international fashion industry, America’s first big business boom. That is, after America’s indigenous populations were forcibly removed from their long inhabited land in order to cultivate the fertile land for these plantations.

India’s Decolonial Leaders

History also shows that local textile and fashion production can free sacrifice zones from their hostage position. During the Indian fight for independence from the British, Mohandas Gandhi helped spur the khadi movement, which sought to boycott cloth manufactured industrially in Britain, promoting the spinning of khadi for rural self-employment and self-reliance. This constructed the framework for the larger Swadeshi movement, now known as the 'Make in India' campaign.

The origins of the Swadeshi movement propagated the idea to use only goods produced in India, and burn British-made goods. Khadi, a hand-spun, hand-woven Indian cotton, is synonymous with Indian independence today.

Leaders continue to establish an equitable understanding of both land and labour, and in doing so, whether they know it or not, they are helping to decolonize the industry. Today, Indian leaders such as Vandana Shiva are working with small farmers to save indigenous varieties of seeds, and wage a war against GMO companies like Monsanto.

Nishanth Chopra of Oshadi Collective has created a regenerative fashion supply chain by creating a chain in which farmers regeneratively grow cotton, local weavers turn it into textiles, with even a natural dyeing collective and block printing studio on site. As Chopra said in a recent Vogue feature, “I didn’t even know it was called ‘regenerative ag’ at the time,” he says. “I just thought it was ancient Indian farming.”

The Kheti Virasat Mission in Punjab is rooted in the mission of reviving the charkha, the type of Indian spinning wheel referenced in the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, as well as organic farming, conservation of water, biodiversity conservation, seed conservation and more. In a recent documentary about the organization, Kheti Virasat Mission’s Associate Director Rupsi Garg notes the ill impacts of the Green Revolution in Punjab, including the loss of organic khadi production on farms. For its benign name, the Green Revolution marked the abandonment of traditional farming methods during the 1960s and 1970s, notably in Punjab. This national program was backed by advisers from the United States and other countries, and initiated Indian farmers to grow with pesticides, high-yield seeds, non-indigenous varieties, and a lack of crop rotation, all with the goal of increasing yields and production.

Although the production of wheat and rice initially doubled due to this initiative, farmers faced the loss of indigenous varieties in crop cultivation, even leading to the extinction of certain varieties. It also caused the land to become infertile with time, leading to the loss of groundwater in many areas.

“Because of the Green Revolution and mechanization, this great tradition of art and craft vanished,” says Umendra Dutt, Executive Director of Kheti Virasat Mission in their documentary. “This is not just making yarn on a charkha (...) it is about making an entire lifestyle rejuvenate."

From Sustainability to Decolonization

If sustainable fashion exists to challenge the way the fashion industry has operated, it must go beyond buying our way into a new reality. We must always question the type of system we are trying to “sustain.” True sustainability means we must decolonize fashion. After all, we can’t expect to fix a problem with the same culture that has created it. So, what does it mean then, to decolonize?

To decolonize the fashion industry is to address wealth inequality. The fashion industry cannot operate without the high-skilled labour of garment workers, yet CEOs make millions off the backs of those that earn the least. It’s not capitalists who create capital, it’s the labour behind the label. The sustainable fashion movement must park a key shift on how we view labour. Garment workers are not expendable. Garment workers are artisans, and fashion is art, not a disposable commodity.

To decolonize the fashion industry is to also reorient metrics of success beyond the idea of unlimited, exponential monetary growth through the extraction and exploitation of finite resources and human labour. The sustainable fashion movement must explore business models that are rooted in circularity and longevity. To decolonize the fashion industry is to dismantle a system predicated on speed, coming at the expense of quality, the environment, and garment workers’ rights.

The sustainable fashion movement must go beyond a model that is rooted in arbitrary trends, and champion a culture of personal style and individuality, rather than exasperating a consumer culture based on trends and cheap goods that will last a few months at most. To decolonize fashion is therefore also to interrogate power and hierarchy, a conversation that demands an intersectional approach that is tied to class, gender, race, and more.

Who has access and agency in this space? And who is stripped of it? The sustainable fashion movement must centre Black, Indigenous, People of Colour (BIPOC) voices as leading actors. These communities have nearly always been historically sustainable, despite the colonial hangover their cultures have experienced. To decolonize the fashion industry is therefore in essence to return to BIPOC knowledge. Regenerative agriculture, the use of natural fibres that frame fashion as a product of agriculture, and localized economies are not new modalities. They were the traditional practices of many BIPOC cultures before colonial modes of agriculture, predicated on output and the loss of indigeneity, were introduced.

Sustainability isn’t about reinventing the wheel – it’s about following the lead of the cultures that have always held regenerative, symbiotic relationships to the planet.

That’s to say, sustainability is decolonization.

Online publication: 23 November 2020