REGENERATIVE FASHION: THERE CAN BE NO OTHER

Where sustainability and fairness come together as one

For decades it has been clear that industrial fashion is much too hard on our physical environment. It is also a significant cause of global warming, greater even than the world's production of steel. In 2018, State of Fashion mounted a full-blown event to examine the problems, and to explore solutions. Their event, dubbed 'Searching for the New Luxury’, pulled together the latest initiatives from around the world in the race to reduce the size of fashion's ecological footprint.

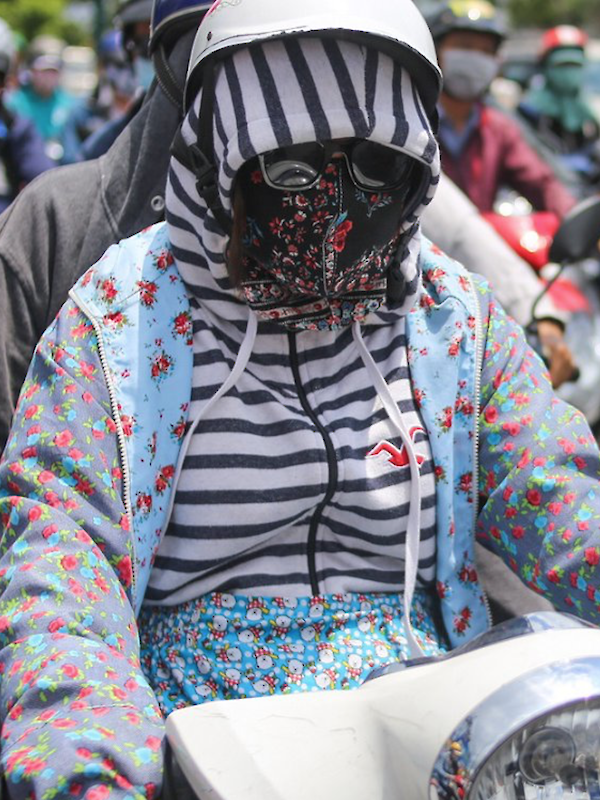

Industrial fashion also earns a miserable failing grade when it comes to labour issues. Since the Rana Plaza factory collapsed in 2013 in Bangladesh, killing more than 1,200 and injuring more than 2,500 garment workers, heedlessness towards fashion labourers has been exposed, dramatically and repeatedly. Reformers are fighting to improve their wages and working conditions. That there is still a long way to go was made evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when these workers were treated as disposable, just as the fashions they make. With clothing consumption levels in decline, millions were tossed out and onto the streets without a safety net.

Strategies to revise fashion are based primarily on these two issues: material (including energy) and labour. As laudable and important as these efforts are, they are not sufficient to solve the crisis. Why not? First, the current framework for fashion sustainability can only result in 'fashion lite': lowered levels of consumption of the earth but otherwise business as usual. The problem is that an engine of growth drives the business, and expansion cancels out material gains made while exploitation remains the mode of operation. The second problem is that better pay and working conditions do not automatically result in fairness. When tens of millions of people around the world, most of them women, are chained to unbridled industrial fashion, this is in itself not fair. Getting more people of colour on catwalks and in boardrooms cannot rectify this greater problem.

More profound change is needed. Coming to terms with the fashion crisis means constructing a path where sustainability and fairness come together as one. By taking into account the vaster implications of the fashion system for nations, cultures, and peoples outside the West, the current framework for fashion sustainability can be revised. This first Intervention in the State of Fashion 2020 program calls attention to a new, more integrated approach.

Deeply flawed definition

To envision this new approach, the writings by Georg Simmel (1858-1918) are pivotal. Simmel is known by fashion theorists for having penned one of the first definitions of fashion. A gentleman of private means and higher social rank, he noted that European fashionable dress was different from all other dress systems on the face of the earth. He noted that "fashion does not exist in tribal and classless societies" because social hierarchy is absent. He perceived that hierarchy drives style change. According to Simmel's definition, change was the central characteristic of fashion. Since then, 'style change through time', has remained central in definitions of fashion and continues to be standard fare in fashion education.

A philosopher and early sociologist, Simmel's research was from the armchair of personal experience. Curiously, however, his claim was never systematically tested but in 2018 a study by American fashion theorists, Welters and Lillethun, revealed it to be false. Change, at varying rates of speed, is found in every clothing system on earth; it is not unique to European fashion.

Simmel's definition is more deeply flawed, however. His claim that Western fashion is unique -- his definition is essentially a celebration of this Western system of dress -- amounts to ethnocentrism. Ethnography reveals that every system of clothing is unique relative to all others, and members of every culture can make the same claim about uniqueness as Simmel did. However, Simmel's ethnocentrism entered Western scholarship in the guise of scientific neutrality.

Even more concerning, his ethnocentrism went paired with a conviction of cultural superiority. Simmel explicitly associated Western fashion with 'higher civilization' and he contrasted it to 'savage' and 'primitive' ways. In essence, therefore, Eurocentrism and white supremacy lie at the core of the commonly accepted definition of fashion.

By classifying the dress systems of the world within a West - Rest binary, Simmel ground a fateful lens through which to see fashion. He wrote at the height of the colonial era, when modes of dressing immediately conveyed a person's position within that polarized system. Everywhere, civilizing the 'less socially advanced' went paired with westernizing their techniques of self-presentation, including not just clothing but also manners. Western ways were imparted through education and religion and the transfer was framed as helpful and generous. There was perceived 'advancement' and 'goodness' in adopting Western ways. 'Progress' was linear, one-way and could not be other than a universal goal. Westernizing was civilizing.

Predicated on inequality

Few students today recognize their personal understanding of fashion in the terms set out by Simmel in a previous era. Fashion dynamics have changed since Simmel's day, and fashion expressions have proliferated everywhere throughout the world. They are no longer singularly Western. In addition, the historical, sociological and political facets of fashion often take a back seat to a focus on design. Nevertheless, the dualism that Simmel observed continues to inform the common understanding of fashion and it is built into current industrial fashion. This Intervention is about learning to see how that dualism, which was evident in Simmel's day, is still present in industrial fashion and thus informs accepted wisdom about fashion. As Hop Hopkins put it, "White supremacy is so pervasive that it's hard to even know that it's there." (2020)

To see it in fashion means digging down to those aspects of fashion that are off the radar: the clothing systems that Simmel classified as 'non-fashion'. They have been situated outside the study of fashion, conceptually erased. The dualism that Simmel perceived as constituting the West in contrast to the Rest, is no longer marked by a geographic boundary because the industrial fashion system has proliferated around the world. Nevertheless, it remains a conceptual dividing line.

This dividing line is found in the current capitalist system, descendant from colonial systems, which is built on growth and expansion. The system is predicated on inequality. Nowhere is this more clear than in 'sacrifice zones': places in the world that are deemed suitable for resource extraction. The 'collateral damage' to living systems, including the indigenous peoples living there, is considered acceptable. Thus it is okay to sacrifice those living systems for the sake of continued economic prosperity and growth. This is the racism built into the economic system. As Hop Hopkins put it, "You can't have climate change without sacrifice zones, and you can't have sacrifice zones without disposable people, and you can't have disposable people without racism" (2020). In sacrifice zones, it is amply clear how environmental destruction and racism merge into one.

Racism is built into the definition of fashion. This amounts to an erasure of the systems of dress belonging to all other peoples on the globe while highlighting the Western, and now globalized, fashion system. This erasure does not just occur conceptually. Fashion production, including the materials and the labour used, creates fashion's sacrifice zones: negated natural and cultural systems considered expendable for the growth of fashion.

Conceptual erasures

There is little research specifically into how fashion feeds off and erodes the clothing systems of other cultures. This is a serious failing consistent with Simmel's dismissal of other cultures and their clothing systems. This is the legacy passed down to students of fashion and reinforced by the media and fashion advertising and marketing. While the appropriation of indigenous design is increasingly being acknowledged as problematic, the relationship between the 'labour pool' for the industrial fashion system and indigenous dress has not yet been addressed. Who are those labourers? What are their indigenous clothing systems? What are the impacts on their dress systems when these women become 'garment workers'? The focus of labour activists, such as the campaign by Fashion Revolution (e.g. Cherrington 2016), is on the individuals who make our clothes, but their cultural membership is not taken into account in the problem of exploitation. While wages are targeted for improvement, the impact of their employment on their culture is left out of consideration. If their skills are derived from making their indigenous crafts, and those crafts are their culture's clothing, what happens to those crafts when their makers become bound to industrial fashion production? To what extent does failure in the craft sector trigger migration to find employment in the garment industry? What is the relationship between the decline of indigenous clothing systems and the expansion of the industrial system? There is both conceptual erasure and erasure-in-fact of non-fashion systems, and fashion is implicated in the decline of cultural diversity in the world.

What are the further consequences of this conceptual erasure? What social mechanisms operate against the viability of indigenous and village life and thus benefit the expansion of the industrial labour pool? The shrinkage of the industrial clothing system, as witnessed during the pandemic lockdown, has led to garment labourers returning to their villages. What is their fate there? We learn of hunger and unemployment. All of this suggests that the responsibility of a fair and moral fashion production system must encompass so much more than ensuring that 'garment workers' receive their final wage when the industrial production system sloughs them off. If fashion and non-fashion are two sides of the fashion coin, the economics of fashion must go far beyond the production and marketing of industrial fashion. It must take into account the economics of non-fashion and also attend to the nexus between fashion and non-fashion: how indigenous clothing systems are rendered non-viable and go extinct, and what happens in indigenous communities when industrial fashions and the western fashion system go global.

Redress

Letting go of the system we all know, in which the ethnocentric understanding of fashion divides dress into fashion and non-fashion, will drastically change the global landscape of dress. Pluriversality will supersede the current dualism. Theorists will set about revising textbooks and fashion history will become multiple in its re-writing.

Redress involves attending to the voices that have been silenced within the non-fashion category. It will revise the bonds between fashion and non-fashion until the distinction no longer exists and fashion diversity becomes the new normal. Redress means the vibrant (re-) burgeoning of systems of dress around the globe. It means not just giving other ethnicities a place at the fashion table, but acknowledging that they have their own table. It means eliminating the sacrifice zones of fashion and all other sacrifice zones that destroy the environments (natural and cultural) in which peoples practice their indigenous systems of dress. Respect and caring will guide the processes of fashion. Redress requires de-linking fashion from the globally dominant economic system.

This Intervention proposes that successful efforts to attain a fair and sustainable fashion must step beyond 'reducing', 'improving' and 'greater efficiency' within 'business as usual'. Getting beyond the blinkered focus on industrial fashion means acknowledging the validity of other systems that have been negated and erased. This opens the radical possibility of regenerative fashion: a qualitative step beyond reducing the negative impacts of the fashion industry, and working towards clothing production that is restorative for both nature and cultures. Regenerative agriculture restores and enriches physical environments. It often begins a willingness to listen to silenced voices and to learn age-old, successful indigenous strategies. Recognizing non-fashion systems may contribute positively to new strategies currently being sought to make fashion sustainable.

Published online: 15 October 2020

Glossary

Download Glossary here.

Selected References

Lead video: film van Ompufino

Cherrington, Rosy, 2016. 'Fashion Revolution 'Who Made Your Clothes' Campaign Reveals Fashion Brands With Supply Chain Transparency'.

Huffpost Sustainable Fashion.

Holthaus, Eric. 2020. “Why Climate Change is a Civil Rights Battle.”

The Correspondent, 18 juni.

Hopkins, Hop. 2020. “Racism is Killing the Planet: The Ideology of White Supremacy Leads the Way toward Disposable People and a Disposable Natural World.”

Sierra: The National Magazine of the Sierra Club, 8 juni.

Simmel, Georg. "Fashion".

American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 62, No. 6 (May, 1957), pp. 541-558. The University of Chicago Press

Welters, Linda, and Abby Lillethun. 2018. Fashion History, a Global View.

New York, NY: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.